|

|

Donald Culross Peattie was a botanist, naturalist, and author; active in the United States Culross Peattie was a botanist, naturalist, and author; active in the United States

in the first half of the 20th century. The following images and descriptions come from in the first half of the 20th century. The following images and descriptions come from

his two-volume work: A Natural History of Trees of North America, first published in 1948, his two-volume work: A Natural History of Trees of North America, first published in 1948,

with illustrations by Paul Landacre included with the 1950 edition. with illustrations by Paul Landacre included with the 1950 edition.

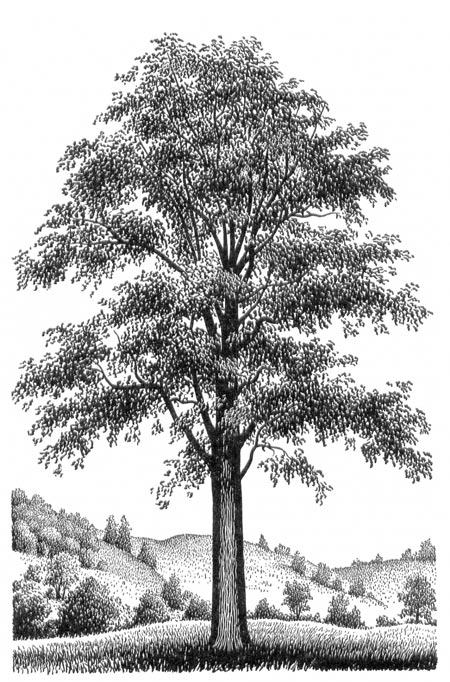

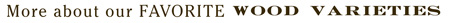

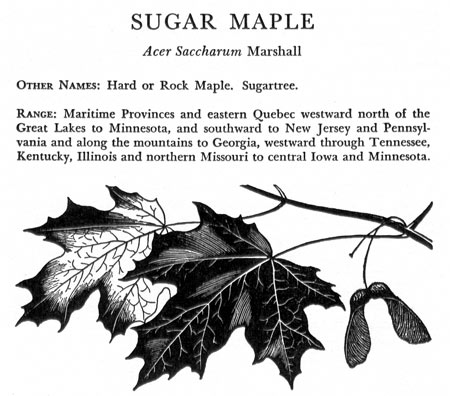

"Under forest conditions, Sugar Maple may grow to 120 feet, with a 3- or 4-foot trunk clear "Under forest conditions, Sugar Maple may grow to 120 feet, with a 3- or 4-foot trunk clear

of branches half the way--a cylinder of nearly knot-free wood almost unrivaled among our of branches half the way--a cylinder of nearly knot-free wood almost unrivaled among our

hardwoods. It is immensely strong and durable, especially the whitish sapwood called by the hardwoods. It is immensely strong and durable, especially the whitish sapwood called by the

lumberman Hard Maple ; a marble floor in a Philadelphia store wore out before a Hard Maple lumberman Hard Maple ; a marble floor in a Philadelphia store wore out before a Hard Maple

flooring laid there at the same time. Few are the standard commercial uses for lumber where flooring laid there at the same time. Few are the standard commercial uses for lumber where

Hard Maple does not figure, either at the top of the list or high on it. Tough and resistant to Hard Maple does not figure, either at the top of the list or high on it. Tough and resistant to

shock, it becomes smoother, not rougher, with much usage-- as you will notice if you look at shock, it becomes smoother, not rougher, with much usage-- as you will notice if you look at

an old-fashioned rolling pin. an old-fashioned rolling pin.

And Sugar Maple can produce some notable fancy grains... Familiar to all is the figure And Sugar Maple can produce some notable fancy grains... Familiar to all is the figure

displayed by curly Maple, for it is the wood used for the backs of fine fiddles. Produced by displayed by curly Maple, for it is the wood used for the backs of fine fiddles. Produced by

dips in the fibers, it gives a striped effect that the violin makers insist on procuring, rare dips in the fibers, it gives a striped effect that the violin makers insist on procuring, rare

though the figure is. In the age when an American made his own gunstocks, curly Maple though the figure is. In the age when an American made his own gunstocks, curly Maple

was his favorite. was his favorite.

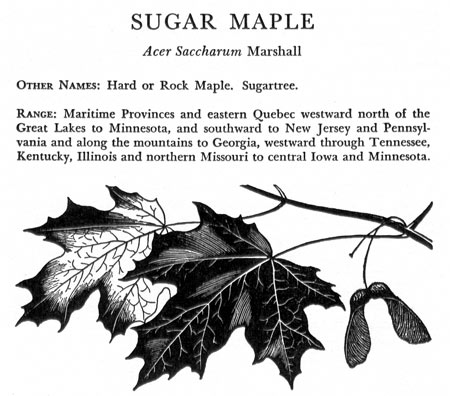

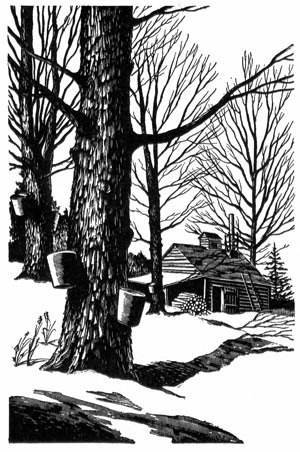

Plant physiologists tell us that the very glory of Maple's autumnal leaves in due in part to Plant physiologists tell us that the very glory of Maple's autumnal leaves in due in part to

the sweetness of [its] sap... That sweetness amounts in the Sugar Maple to 2 percent or even the sweetness of [its] sap... That sweetness amounts in the Sugar Maple to 2 percent or even

6 percent of the sap. But of course the yield of sap varies much with the method of tapping, 6 percent of the sap. But of course the yield of sap varies much with the method of tapping,

the size of the tree, and the given season... the size of the tree, and the given season...

The early colonists, both English and French, learned the art of sugaring, of course, from The early colonists, both English and French, learned the art of sugaring, of course, from

the red man for whom Maple sugar was the only sweet. The Indians had their sugar camps, the red man for whom Maple sugar was the only sweet. The Indians had their sugar camps,

just as the white man... Their method was to slash a gash in the tree, when the sap was rising, just as the white man... Their method was to slash a gash in the tree, when the sap was rising,

and insert a hollow reed stem or a spile of hollow Sumac twig or a funnel of bark. The sap was and insert a hollow reed stem or a spile of hollow Sumac twig or a funnel of bark. The sap was

then allowed to pour from the spile into a bark bowl or bucket or a gourd shell, and this in turn then allowed to pour from the spile into a bark bowl or bucket or a gourd shell, and this in turn

was emptied into a large vessel of Elm bark or a tree trunk hollowed out to form a trough. Having was emptied into a large vessel of Elm bark or a tree trunk hollowed out to form a trough. Having

no metal vessels to endure direct contact with the fire, the Indians let the sap freeze and took off no metal vessels to endure direct contact with the fire, the Indians let the sap freeze and took off

the ice from time to time (thus, in effect concentrating the syrup), or they boiled it by dropping the ice from time to time (thus, in effect concentrating the syrup), or they boiled it by dropping

hot stones into the sap troughs. Some of the hot syrup might then be poured out on the snow hot stones into the sap troughs. Some of the hot syrup might then be poured out on the snow

for the children, who ate it as a sort of candy. But for future use, the sugar was stored in bark for the children, who ate it as a sort of candy. But for future use, the sugar was stored in bark

boxes. Often on the frontier, "barks of sugar" were bartered from the Indians by the pioneers. boxes. Often on the frontier, "barks of sugar" were bartered from the Indians by the pioneers.

[...] [...]

The flavor of sugar-making as an old-time Vermonter knows it is given in the following passage The flavor of sugar-making as an old-time Vermonter knows it is given in the following passage

contributed by Thomas Ripley, lumberman, Yale man (class of 1888), and author of the delectable contributed by Thomas Ripley, lumberman, Yale man (class of 1888), and author of the delectable

volume A Vermont Boyhood: volume A Vermont Boyhood:

'The Spring snows begin to melt, leaving soft, wonderful-smelling bare patches about 'The Spring snows begin to melt, leaving soft, wonderful-smelling bare patches about

the Maple trunks in the sugar bush. The Vermont farmer cocks his eye at the sun in its the Maple trunks in the sugar bush. The Vermont farmer cocks his eye at the sun in its

northwest passage, feels something stirring in his insides and turns his thoughts to the northwest passage, feels something stirring in his insides and turns his thoughts to the

sugar shanty and the sap buckets. A nippy frost at night freezes little blobs of ice at the sugar shanty and the sap buckets. A nippy frost at night freezes little blobs of ice at the

ends of the Maple twigs. A prodigal sun melts them and warms the bare patches. 'Sap's ends of the Maple twigs. A prodigal sun melts them and warms the bare patches. 'Sap's

runnin'!' The mysterious signal is sounded and the annual miracle is on. every boy and runnin'!' The mysterious signal is sounded and the annual miracle is on. every boy and

girl in the village knows that sap's runnin'. Teacher knows it, too. For the kinship with girl in the village knows that sap's runnin'. Teacher knows it, too. For the kinship with

the Maples, human sap as well as vegetable is rising. the Maples, human sap as well as vegetable is rising.

'A wonderful transformation takes place in the sugar bush; with a stroke of heaven's 'A wonderful transformation takes place in the sugar bush; with a stroke of heaven's

wand, the winter-bound grove becomes a fairyland of blue and gold, picked out with red wand, the winter-bound grove becomes a fairyland of blue and gold, picked out with red

and green sap buckets like Christmas tree ornaments. It was good to see and hear the and green sap buckets like Christmas tree ornaments. It was good to see and hear the

drip of the sap. It seems to me that I can remember particular days when the sap ran in drip of the sap. It seems to me that I can remember particular days when the sap ran in

a trickling stream, so bounteous was the store. a trickling stream, so bounteous was the store.

'With the advent of our pioneer ancestors, the american passion for efficiency set in... 'With the advent of our pioneer ancestors, the american passion for efficiency set in...

It seems there were various ways of 'boiling down,' each succeeding way an improvement It seems there were various ways of 'boiling down,' each succeeding way an improvement

on the old. In my boyhood, I read of the 'good old times' when two logs were laid parallel on the old. In my boyhood, I read of the 'good old times' when two logs were laid parallel

to each other ('side by each,' as undoubtedly it was described), between which the fire was to each other ('side by each,' as undoubtedly it was described), between which the fire was

lighted. And over the fire a row of kettles, a big one at the end, to receive the sap, a smaller lighted. And over the fire a row of kettles, a big one at the end, to receive the sap, a smaller

one next and then a still smaller one down to the littlest of all. Dipping from kettle to kettle, one next and then a still smaller one down to the littlest of all. Dipping from kettle to kettle,

the finished syrup was dipped from the little kettle. the finished syrup was dipped from the little kettle.

'The long fire and the row of kettles has given way to the march of improvement before I 'The long fire and the row of kettles has given way to the march of improvement before I

ever came on the scene. I seem to remember a big flat receptacle over a fire, an evaporator, ever came on the scene. I seem to remember a big flat receptacle over a fire, an evaporator,

I think it was called, into which the sap was poured. It bubbled and threw off the most I think it was called, into which the sap was poured. It bubbled and threw off the most

delightful smells while the fire was stoked underneath with the dry 'dead and down' wood delightful smells while the fire was stoked underneath with the dry 'dead and down' wood

that the bush yielded. though it was watched and skimmed from time to time, a lot of smoke that the bush yielded. though it was watched and skimmed from time to time, a lot of smoke

and cinders floated into the boiling, and the finished product emerged a bit gritty, coarse in and cinders floated into the boiling, and the finished product emerged a bit gritty, coarse in

texture when compared with the modern stuff, but with the tang of woodsmoke in it. texture when compared with the modern stuff, but with the tang of woodsmoke in it.

'As the boiling down proceeded, the boys and girls crowded in for 'sugaring off' parties. 'As the boiling down proceeded, the boys and girls crowded in for 'sugaring off' parties.

Big dishpans and earthenware bowls were packed hard with snow on which the hot syrup, Big dishpans and earthenware bowls were packed hard with snow on which the hot syrup,

fresh from the boiling, was spooned. It coagulated into the moist heavenly dew. Patterns fresh from the boiling, was spooned. It coagulated into the moist heavenly dew. Patterns

were made, preferably hearts and arrows with initials of boy swain or girl flutterer.'" were made, preferably hearts and arrows with initials of boy swain or girl flutterer.'"

-A Natural History of Trees of Eastern and Central North America pp.453-460 -A Natural History of Trees of Eastern and Central North America pp.453-460

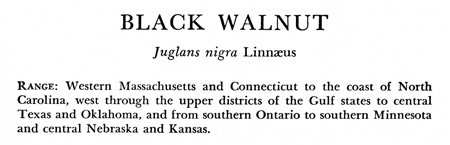

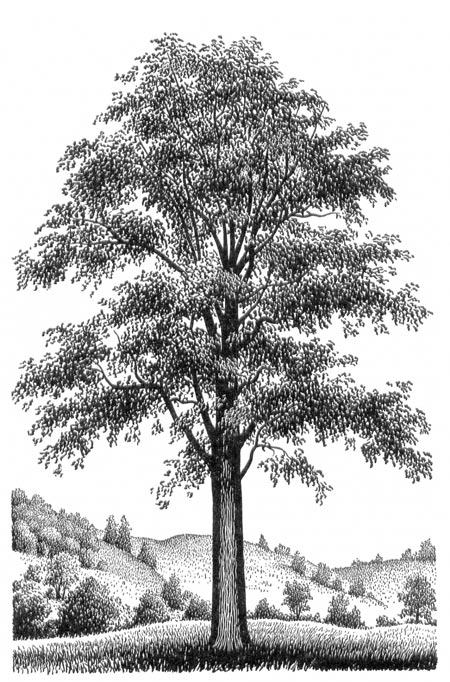

"The home of the Black Walnut is the deep rich soil of bottom-lands and fertile hillsides; it grew "The home of the Black Walnut is the deep rich soil of bottom-lands and fertile hillsides; it grew

abundantly throughout the primeval forests of America. abundantly throughout the primeval forests of America.

[...] [...]

"Of all the native nut trees of America, the Black Walnut is the most valuable save only "Of all the native nut trees of America, the Black Walnut is the most valuable save only

the Pecan, and in the traditions of pioneer life and rustic childhood it is even more famous. In the Pecan, and in the traditions of pioneer life and rustic childhood it is even more famous. In

a more innocent age nutting parties were the most highly prized of children's festivities in a more innocent age nutting parties were the most highly prized of children's festivities in

Autumn, throughout the eastern forest belt... Autumn, throughout the eastern forest belt...

[...] [...]

"Black Walnut provides the finest cabinet wood in North America. The colonists understood "Black Walnut provides the finest cabinet wood in North America. The colonists understood

its utilization from the first--indeed were exporting it to England from Virginia as early as 1610 its utilization from the first--indeed were exporting it to England from Virginia as early as 1610

--without, however, being able to develop its beautiful figured grains as can be done now with --without, however, being able to develop its beautiful figured grains as can be done now with

veneers. On the contrary, they employed solid Walnut wood and often had so little appreciation veneers. On the contrary, they employed solid Walnut wood and often had so little appreciation

of it as a grain beautiful in its own right that they painted its surface. Walnut was used in every of it as a grain beautiful in its own right that they painted its surface. Walnut was used in every

sort of homemade furniture of the Colonial and Federal periods, but seldom in fine styles. By the sort of homemade furniture of the Colonial and Federal periods, but seldom in fine styles. By the

time that appreciation of rare grains was born and the rage for Walnut really began (1830 to 1860), time that appreciation of rare grains was born and the rage for Walnut really began (1830 to 1860),

machine-made furniture, turning out Empire, Victorian, and Revival styles, ruined many a fine machine-made furniture, turning out Empire, Victorian, and Revival styles, ruined many a fine

piece of wood. Then, as the final irony, when styles improved, Walnut had become comparatively piece of wood. Then, as the final irony, when styles improved, Walnut had become comparatively

rare. rare.

"There is so little Black Walnut in the forest now (except in the southern Appalachians) that it "There is so little Black Walnut in the forest now (except in the southern Appalachians) that it

is sought by lumbermen in a door-to-door hunt throughout the countryside... is sought by lumbermen in a door-to-door hunt throughout the countryside...

"But in Pioneer times these giants were so abundant in our earth that they were used for such "But in Pioneer times these giants were so abundant in our earth that they were used for such

humble things as snake-rail fences; probably many of the rails that Lincoln split were Walnut. humble things as snake-rail fences; probably many of the rails that Lincoln split were Walnut.

Millions of railroad ties have, on account of its durability in contact with soil, been made of this Millions of railroad ties have, on account of its durability in contact with soil, been made of this

now valuable wood. Cradles were almost exclusively made of Walnut in our heroic era. For gun- now valuable wood. Cradles were almost exclusively made of Walnut in our heroic era. For gun-

stocks it was, and is, unsurpassed, since no other wood has less jar or recoil; it never warps or stocks it was, and is, unsurpassed, since no other wood has less jar or recoil; it never warps or

shrinks; it is light in proportion to its strength, never splinters and, no matter how long it is shrinks; it is light in proportion to its strength, never splinters and, no matter how long it is

carried in the hand, will not irritate the palm, with its wonderful satiny surface. In every war, the carried in the hand, will not irritate the palm, with its wonderful satiny surface. In every war, the

United states government has made a fresh raid upon Black Walnut for gunstocks. United states government has made a fresh raid upon Black Walnut for gunstocks.

[...] [...]

"There is a significant difference between the solid Walnut furniture of the pioneers and the "There is a significant difference between the solid Walnut furniture of the pioneers and the

modern Walnut veneers. The old trees were mostly forest-grown, hence slow-growing; it took modern Walnut veneers. The old trees were mostly forest-grown, hence slow-growing; it took

almost 100 years to produce a Walnut of timber size under those conditions, and the boards show almost 100 years to produce a Walnut of timber size under those conditions, and the boards show

a straight grain and very dark heartwood. Thus the old-time Walnut furniture often has a somber, a straight grain and very dark heartwood. Thus the old-time Walnut furniture often has a somber,

heavy look, lacking refinement either in grain or design. But there is an honesty about it that links heavy look, lacking refinement either in grain or design. But there is an honesty about it that links

us to our past. Perhaps the best example of the middle period of American furniture is the great us to our past. Perhaps the best example of the middle period of American furniture is the great

secretary of President Jackson, to be seen at The Hermitage near Nashville, at which he wrote secretary of President Jackson, to be seen at The Hermitage near Nashville, at which he wrote

his sizzling and misspelled correspondence." his sizzling and misspelled correspondence."

-A Natural History of Trees of Eastern and Central North America pp.122-125 -A Natural History of Trees of Eastern and Central North America pp.122-125

| |

Culross Peattie was a botanist, naturalist, and author; active in the United States

Culross Peattie was a botanist, naturalist, and author; active in the United States in the first half of the 20th century. The following images and descriptions come from

in the first half of the 20th century. The following images and descriptions come from  his two-volume work: A Natural History of Trees of North America, first published in 1948,

his two-volume work: A Natural History of Trees of North America, first published in 1948, with illustrations by Paul Landacre included with the 1950 edition.

with illustrations by Paul Landacre included with the 1950 edition.

"Under forest conditions, Sugar Maple may grow to 120 feet, with a 3- or 4-foot trunk clear

"Under forest conditions, Sugar Maple may grow to 120 feet, with a 3- or 4-foot trunk clear

of branches half the way--a cylinder of nearly knot-free wood almost unrivaled among our

of branches half the way--a cylinder of nearly knot-free wood almost unrivaled among our

hardwoods. It is immensely strong and durable, especially the whitish sapwood called by the

hardwoods. It is immensely strong and durable, especially the whitish sapwood called by the

lumberman Hard Maple ; a marble floor in a Philadelphia store wore out before a Hard Maple

lumberman Hard Maple ; a marble floor in a Philadelphia store wore out before a Hard Maple

flooring laid there at the same time. Few are the standard commercial uses for lumber where

flooring laid there at the same time. Few are the standard commercial uses for lumber where

Hard Maple does not figure, either at the top of the list or high on it. Tough and resistant to

Hard Maple does not figure, either at the top of the list or high on it. Tough and resistant to

shock, it becomes smoother, not rougher, with much usage-- as you will notice if you look at

shock, it becomes smoother, not rougher, with much usage-- as you will notice if you look at

an old-fashioned rolling pin.

an old-fashioned rolling pin.

And Sugar Maple can produce some notable fancy grains... Familiar to all is the figure

And Sugar Maple can produce some notable fancy grains... Familiar to all is the figure

displayed by curly Maple, for it is the wood used for the backs of fine fiddles. Produced by

displayed by curly Maple, for it is the wood used for the backs of fine fiddles. Produced by

dips in the fibers, it gives a striped effect that the violin makers insist on procuring, rare

dips in the fibers, it gives a striped effect that the violin makers insist on procuring, rare

though the figure is. In the age when an American made his own gunstocks, curly Maple

though the figure is. In the age when an American made his own gunstocks, curly Maple

was his favorite.

was his favorite.

Plant physiologists tell us that the very glory of Maple's autumnal leaves in due in part to

Plant physiologists tell us that the very glory of Maple's autumnal leaves in due in part to

the sweetness of [its] sap... That sweetness amounts in the Sugar Maple to 2 percent or even

the sweetness of [its] sap... That sweetness amounts in the Sugar Maple to 2 percent or even

6 percent of the sap. But of course the yield of sap varies much with the method of tapping,

6 percent of the sap. But of course the yield of sap varies much with the method of tapping,

the size of the tree, and the given season...

the size of the tree, and the given season...

The early colonists, both English and French, learned the art of sugaring, of course, from

The early colonists, both English and French, learned the art of sugaring, of course, from

the red man for whom Maple sugar was the only sweet. The Indians had their sugar camps,

the red man for whom Maple sugar was the only sweet. The Indians had their sugar camps,

just as the white man... Their method was to slash a gash in the tree, when the sap was rising,

just as the white man... Their method was to slash a gash in the tree, when the sap was rising,

and insert a hollow reed stem or a spile of hollow Sumac twig or a funnel of bark. The sap was

and insert a hollow reed stem or a spile of hollow Sumac twig or a funnel of bark. The sap was

then allowed to pour from the spile into a bark bowl or bucket or a gourd shell, and this in turn

then allowed to pour from the spile into a bark bowl or bucket or a gourd shell, and this in turn

was emptied into a large vessel of Elm bark or a tree trunk hollowed out to form a trough. Having

was emptied into a large vessel of Elm bark or a tree trunk hollowed out to form a trough. Having

no metal vessels to endure direct contact with the fire, the Indians let the sap freeze and took off

no metal vessels to endure direct contact with the fire, the Indians let the sap freeze and took off

the ice from time to time (thus, in effect concentrating the syrup), or they boiled it by dropping

the ice from time to time (thus, in effect concentrating the syrup), or they boiled it by dropping

hot stones into the sap troughs. Some of the hot syrup might then be poured out on the snow

hot stones into the sap troughs. Some of the hot syrup might then be poured out on the snow

for the children, who ate it as a sort of candy. But for future use, the sugar was stored in bark

for the children, who ate it as a sort of candy. But for future use, the sugar was stored in bark

boxes. Often on the frontier, "barks of sugar" were bartered from the Indians by the pioneers.

boxes. Often on the frontier, "barks of sugar" were bartered from the Indians by the pioneers.

[...]

[...]

The flavor of sugar-making as an old-time Vermonter knows it is given in the following passage

The flavor of sugar-making as an old-time Vermonter knows it is given in the following passage

contributed by Thomas Ripley, lumberman, Yale man (class of 1888), and author of the delectable

contributed by Thomas Ripley, lumberman, Yale man (class of 1888), and author of the delectable

volume A Vermont Boyhood:

volume A Vermont Boyhood:

'The Spring snows begin to melt, leaving soft, wonderful-smelling bare patches about

'The Spring snows begin to melt, leaving soft, wonderful-smelling bare patches about

the Maple trunks in the sugar bush. The Vermont farmer cocks his eye at the sun in its

the Maple trunks in the sugar bush. The Vermont farmer cocks his eye at the sun in its

northwest passage, feels something stirring in his insides and turns his thoughts to the

northwest passage, feels something stirring in his insides and turns his thoughts to the

sugar shanty and the sap buckets. A nippy frost at night freezes little blobs of ice at the

sugar shanty and the sap buckets. A nippy frost at night freezes little blobs of ice at the

ends of the Maple twigs. A prodigal sun melts them and warms the bare patches. 'Sap's

ends of the Maple twigs. A prodigal sun melts them and warms the bare patches. 'Sap's

runnin'!' The mysterious signal is sounded and the annual miracle is on. every boy and

runnin'!' The mysterious signal is sounded and the annual miracle is on. every boy and

girl in the village knows that sap's runnin'. Teacher knows it, too. For the kinship with

girl in the village knows that sap's runnin'. Teacher knows it, too. For the kinship with

the Maples, human sap as well as vegetable is rising.

the Maples, human sap as well as vegetable is rising.

'A wonderful transformation takes place in the sugar bush; with a stroke of heaven's

'A wonderful transformation takes place in the sugar bush; with a stroke of heaven's

wand, the winter-bound grove becomes a fairyland of blue and gold, picked out with red

wand, the winter-bound grove becomes a fairyland of blue and gold, picked out with red

and green sap buckets like Christmas tree ornaments. It was good to see and hear the

and green sap buckets like Christmas tree ornaments. It was good to see and hear the

drip of the sap. It seems to me that I can remember particular days when the sap ran in

drip of the sap. It seems to me that I can remember particular days when the sap ran in

a trickling stream, so bounteous was the store.

a trickling stream, so bounteous was the store.

'With the advent of our pioneer ancestors, the american passion for efficiency set in...

'With the advent of our pioneer ancestors, the american passion for efficiency set in...

It seems there were various ways of 'boiling down,' each succeeding way an improvement

It seems there were various ways of 'boiling down,' each succeeding way an improvement

on the old. In my boyhood, I read of the 'good old times' when two logs were laid parallel

on the old. In my boyhood, I read of the 'good old times' when two logs were laid parallel

to each other ('side by each,' as undoubtedly it was described), between which the fire was

to each other ('side by each,' as undoubtedly it was described), between which the fire was

lighted. And over the fire a row of kettles, a big one at the end, to receive the sap, a smaller

lighted. And over the fire a row of kettles, a big one at the end, to receive the sap, a smaller

one next and then a still smaller one down to the littlest of all. Dipping from kettle to kettle,

one next and then a still smaller one down to the littlest of all. Dipping from kettle to kettle,

the finished syrup was dipped from the little kettle.

the finished syrup was dipped from the little kettle.

'The long fire and the row of kettles has given way to the march of improvement before I

'The long fire and the row of kettles has given way to the march of improvement before I

ever came on the scene. I seem to remember a big flat receptacle over a fire, an evaporator,

ever came on the scene. I seem to remember a big flat receptacle over a fire, an evaporator,

I think it was called, into which the sap was poured. It bubbled and threw off the most

I think it was called, into which the sap was poured. It bubbled and threw off the most

delightful smells while the fire was stoked underneath with the dry 'dead and down' wood

delightful smells while the fire was stoked underneath with the dry 'dead and down' wood

that the bush yielded. though it was watched and skimmed from time to time, a lot of smoke

that the bush yielded. though it was watched and skimmed from time to time, a lot of smoke

and cinders floated into the boiling, and the finished product emerged a bit gritty, coarse in

and cinders floated into the boiling, and the finished product emerged a bit gritty, coarse in

texture when compared with the modern stuff, but with the tang of woodsmoke in it.

texture when compared with the modern stuff, but with the tang of woodsmoke in it.

'As the boiling down proceeded, the boys and girls crowded in for 'sugaring off' parties.

'As the boiling down proceeded, the boys and girls crowded in for 'sugaring off' parties.

Big dishpans and earthenware bowls were packed hard with snow on which the hot syrup,

Big dishpans and earthenware bowls were packed hard with snow on which the hot syrup,

fresh from the boiling, was spooned. It coagulated into the moist heavenly dew. Patterns

fresh from the boiling, was spooned. It coagulated into the moist heavenly dew. Patterns

were made, preferably hearts and arrows with initials of boy swain or girl flutterer.'"

were made, preferably hearts and arrows with initials of boy swain or girl flutterer.'"

-A Natural History of Trees of Eastern and Central North America pp.453-460

-A Natural History of Trees of Eastern and Central North America pp.453-460

"The home of the Black Walnut is the deep rich soil of bottom-lands and fertile hillsides; it grew

"The home of the Black Walnut is the deep rich soil of bottom-lands and fertile hillsides; it grew

abundantly throughout the primeval forests of America.

abundantly throughout the primeval forests of America.

[...]

[...]

"Of all the native nut trees of America, the Black Walnut is the most valuable save only

"Of all the native nut trees of America, the Black Walnut is the most valuable save only

the Pecan, and in the traditions of pioneer life and rustic childhood it is even more famous. In

the Pecan, and in the traditions of pioneer life and rustic childhood it is even more famous. In

a more innocent age nutting parties were the most highly prized of children's festivities in

a more innocent age nutting parties were the most highly prized of children's festivities in

Autumn, throughout the eastern forest belt...

Autumn, throughout the eastern forest belt...

[...]

[...]

"Black Walnut provides the finest cabinet wood in North America. The colonists understood

"Black Walnut provides the finest cabinet wood in North America. The colonists understood

its utilization from the first--indeed were exporting it to England from Virginia as early as 1610

its utilization from the first--indeed were exporting it to England from Virginia as early as 1610

--without, however, being able to develop its beautiful figured grains as can be done now with

--without, however, being able to develop its beautiful figured grains as can be done now with

veneers. On the contrary, they employed solid Walnut wood and often had so little appreciation

veneers. On the contrary, they employed solid Walnut wood and often had so little appreciation

of it as a grain beautiful in its own right that they painted its surface. Walnut was used in every

of it as a grain beautiful in its own right that they painted its surface. Walnut was used in every

sort of homemade furniture of the Colonial and Federal periods, but seldom in fine styles. By the

sort of homemade furniture of the Colonial and Federal periods, but seldom in fine styles. By the

time that appreciation of rare grains was born and the rage for Walnut really began (1830 to 1860),

time that appreciation of rare grains was born and the rage for Walnut really began (1830 to 1860),

machine-made furniture, turning out Empire, Victorian, and Revival styles, ruined many a fine

machine-made furniture, turning out Empire, Victorian, and Revival styles, ruined many a fine

piece of wood. Then, as the final irony, when styles improved, Walnut had become comparatively

piece of wood. Then, as the final irony, when styles improved, Walnut had become comparatively

rare.

rare.

"There is so little Black Walnut in the forest now (except in the southern Appalachians) that it

"There is so little Black Walnut in the forest now (except in the southern Appalachians) that it

is sought by lumbermen in a door-to-door hunt throughout the countryside...

is sought by lumbermen in a door-to-door hunt throughout the countryside...